Workers of the World, Please See Our Web Site

From: New York Times

By JOSEPH BERGER

Published: May 22, 2011

You can still be a card-carrying Communist in New York, but these days committed Communists usually register online.

Jared Abbott, left, Andrew Porter and Frank Llewellyn, all Democratic Socialists, after a rally on living wages.

Michelle V. Agins/The New York Times

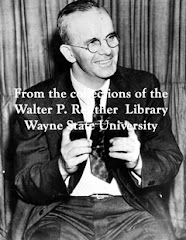

Billy Wharton, a co-chairman of the Socialist Party, in his office on Lafayette Street.

“We actually have a card, but we don’t make a big deal of it,” said Sam Webb, the national chairman of the Communist Party U.S.A.

The Socialist Party U.S.A. does distribute red cards to members willing to “subscribe to the principles” of the party, but another leftist group, the Democratic Socialists of America, prefers online registration, with members using a virtual shopping cart to pay yearly dues of about $60 by credit card — Marx be damned.

In some ways, the Left remains locked in place. Its three major national parties are still confined to cramped Manhattan offices that are plastered with gaudy posters and honeycombed with pamphlets for distribution and envelopes for stuffing.

But in other ways the landscape has changed significantly. All three parties are finding the Internet to be a fruitful recruiting tool and believe their message has been given a fresh, beguiling appeal by the failures of capitalist symbols like Lehman Brothers and by debacles like the billions of dollars in securities tied to subprime mortgages.

“The economic crisis of 2008 gave us new life,” said Billy Wharton, a co-chairman of the Socialist Party, who grew enamored of socialism while battling tuition increases as a student at the College of Staten Island. “We have ideas for resolving the economic crisis, and people began to listen to them.”

Rather than trumpeting membership numbers, the parties, embracing the norms of the digital era, prefer to discuss the number of hits on their Web sites and Facebook pages. And philosophically, they take a kind of I-told-you-so schadenfreude in statistics that indicate a growing gap between the rich and the poor, with top chief executives now making 275 times as much as the average proletarian.

Still, it is hard to imagine that the parties have inherited a revolutionary tradition once so popular that in the 1932 presidential election, Norman Thomas, the Socialist candidate, garnered 884,000 votes and William Z. Foster, the Communist candidate, had over 100,000. But then again, after the breakup of the Soviet Union and the collapse of socialist republics in Eastern Europe, some people may be surprised to learn that these parties are still around.

All three have greatly shrunk from their heydays. The Socialist Party has about 1,000 members nationally. The Communists claim 2,000. The Democratic Socialists, which for many years included luminaries like Michael Harrington and Irving Howe, have about 6,000.

“It’s not easy to make political progress outside the two-party structure because people don’t want to waste their votes,” said Frank Llewellyn, 62, the national director of the Democratic Socialists, who became a socialist as a result of the civil rights and antiwar movements.

Rather than battling for power through elections, all three parties try to sway the national conversation through coalitions with labor unions and other mainstream organizations. Both socialist groups turned out at City Hall this month to protest budget cuts, at a rally that was largely organized by the unions.

But on matters of principle, the leftist parties diverge. All three oppose President Obama’s health care program, seeing it as a giveaway to insurance companies and preferring either a single-payer government plan or a socialized system like that of Britain, where doctors work for the government.

The Socialists sometimes do have candidates who run in states where the rules for getting on the ballot are not too onerous; Greg Pason, the national secretary, ran for governor of New Jersey in 2009. But the Democratic Socialists see that effort as futile and prefer endorsements; they supported David N. Dinkins and Ruth W. Messinger in their mayoral bids in New York City.

The parties’ enduring character is obvious in visits to their offices. The Socialist Party is housed in a tumbledown building on Lafayette Street known informally as the “Peace Pentagon” or the A. J. Muste building, not because the name approximates its mildewed atmosphere but because Mr. Muste was a benefactor of the peace groups that the building houses. The Democratic Socialists even have a foothold on Wall Street, with cluttered offices in a building on Maiden Lane. It is not because Wall Street has suddenly adopted a philosophy of “to each according to his own needs.”

“It’s cheap,” Mr. Llewellyn explained. “This is an area of the city where you get the best deals.”

The Communists even own the means of production — they lease out their eight-story building on West 23rd Street to other left-wing organizations. The party has the most decorous space, having redesigned its office with glass walls and tall windows.

“We’re not up to some nefarious business we have to hide from the American government,” said Libero Della Piana, 38, the party’s communications director.

Physical space matters less these days than virtual space. All three groups have lively Web sites that flaunt their philosophies and histories. Mr. Della Piana, the child of an Italian anarchist, boasts that the Communists’ news site has 25,000 unique visitors a week; before it stopped publishing in the late 1960s, its newspaper, The Daily Worker, was read by just 5,000 subscribers. In 2010, he said, 700 prospective members applied through the Web site.

Recent disclosures of capitalist excesses have given the parties a second wind after the collapse of the Soviet Union suggested the bankruptcy of collectivist philosophy. Mr. Llewellyn said that since 2007 his party’s membership had increased by 50 percent, to 6,000.

“People see the consequences of unregulated markets, greed, a lack of checks on the power of the private flow of capital to drive the economy and undermine jobs,” Mr. Llewellyn said.

Mr. Webb, who joined the Communists in the 1970s, likes to emphasize the party’s rich history, including the fight against McCarthyism and the volunteers who helped the Spanish Republicans battle the Fascists, rather than more unpleasant episodes like the case of the American Communist Julius Rosenberg, who spied for the Soviet Union.

Mr. Della Piana says the Soviet Union’s dissolution freed the party to be more ideological because “no one could ever say again we were puppets.”

“We have a whole generation of young people attracted to the idea of communism without the baggage of the cold war,” he said.

After declining to 250 members in 1980, the Socialist Party’s membership has quadrupled, Mr. Wharton said. He was even asked to appear on a Fox affiliate when conservatives raised suspicions that Mr. Obama was a socialist.

“They thought I’d go on and on and actually support the policies of President Obama,” said Mr. Wharton, 42, a General Educational Development, or G.E.D., teacher in Brooklyn. “The question was ‘Is he a socialist?’ and my answer was ‘I’m not sure he’s even a liberal.’ I called him a hedge-fund Democrat.”

None of the parties view their existence as futile — immersing themselves in everyday local battles, they believe, will spread their influence.

“Socialism won’t come to this country until tens of millions decide capitalism doesn’t work for them,” Mr. Webb said. “If you’re a revolutionary, if you’re a socialist, you have to have patience.”

A version of this article appeared in print on May 23, 2011, on page A18 of the New York edition with the headline: Workers of the World, Please See Our Web Site.